Shura begins with the setting of the sun. It is the last time color, or the light of day, will enter into the world of the film. Only darkness remains.

Certainly Toshio Matsumoto’s Shura is a dark film. In fact, that’s an understatement; in Shura, light has ceased to exist. Darkness encloses the actors, and the sets. Each and every shot seems to be crafted in such a way that the screen is almost 50% black. This striking visual scheme certainly fits the mood, which is one of utter desolation and despair.

Gengo (Katsuo Nakamura) is a broke ronin, living with one loyal retainer in a Spartan house with bare walls. He’s sold everything he owns, except his sword, seemingly to “keep” a woman, a low-level geisha named Koman (Yasuko Sanjo) with whom he has fallen in love. In actuality, he is a samurai named Soemon, who needs all the money he can get to pay off a 100 ryo debt. In doing so, he can return to favor with his lord and join 47 other ronin--the 47 samurai (or loyal ronin) of Japan’s national legend.

The catalyst which causes the ensuing tragedy comes when the ronin’s retainer, Hachiemon, arrives with the 100 ryo Gengo needs to buy his way back into the honorable vendetta. It's always money, isn't it? Sango (Juro Kara), a beneficiary of Gengo’s patronage, shows up immediately after this, explaining that Koman is going to be sold to another samurai. Her cost? 100 ryo.

To get to the point: Gengo, after much prodding, spends the 100 ryo he so desperately needs, in order to save Koman, who agrees to marry him. But, there’s a problem. Koman can't be married, at least, not again. Sango is actually Koman’s husband. The two of them have played Gengo, and in doing so have stripped him of his love, his money, and his honor.

Gengo doesn’t take this well.

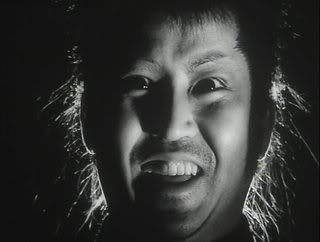

Though he’s initially ruined by the revelation, Gengo soon comes to realize the extent of the dishonor that's been done to him. The rest of the film details Gengo’s all-consuming quest for vengeance, and it does so with bleak, powerful visuals that seem to bring into clear focus the true horror of violence.

To the average viewer of samurai cinema, Gengo’s initial actions hardly seem beyond the pale. He is, after all, a samurai, a member of a cast distinguished by its two swords and its exclusive franchise on violence. That he chooses to wield his swords against those who wronged him seems quite in keeping with the cinematic samurai tradition.

Not so fast, says Matsumoto. Violence is not a clean, sanitized event, and vengeance can never truly be justified. As Gengo becomes consumed by his fury, he becomes less and less a man, and more a demon. When people die by his sword, they die terribly, and the graphic and intense depictions of their deaths only reinforces the brutality of Gengo’s “justice.”

Matsumoto is primarily an experimental filmmaker, with the vast majority of his work done in the genre of the short film. Only four times, to my knowledge, did he make full length features. He’s probably most well known (this is a relative term) as the director of Funeral Parade of Roses, the film that (supposedly) inspired Stanley Kubrick when he made A Clockwork Orange. While Shura is a very straightforward story, elements of Matsumoto’s background in experimental film seem to find their way in. The film is certainly shot by someone who is just as concerned with the visual look as he is with the story itself.

While Shura never dips off into total surrealism, the film remains oneiric throughout. The viewer is never absolutely sure that what he is seeing is actually taking place, or if it is actually a dream. After all, the film starts with a precognitive dream, and more than once the film depicts the contents of Gengo’s mind--how he hopes things might play out--as though they were real. Finally, it’s never really certain if Gengo is becoming “demon-like” with his actions, or if it should be understood like a horror movie, in that Gengo is actually becoming a monster. In a sense, it hardly matters; the evil wrought by Gengo is the evil wrought by man, and the evils against him (there are plenty) are certainly human as well.

To date, Shura doesn’t have a DVD release (that I know of) outside of Asia. It’s a shame, really. Hopefully Masters of Cinema, who released Funeral Parade of Roses in Britain, might look into this one in the future. It would certainly be worth it.

2 comments:

let me read your MA thesis!

I was tempted to describe this film as "David Lynch (circa ERASERHEAD) directing a chamber play. With samurai." That might be a bit sensationalistic, though.

Post a Comment