"Banned for decades! The most notorious Japanese Horror film EVER made!" shouts the cover of Teruo Ishii's Horrors Of Malformed Men, and fans of extreme Japanese cinema could be excused for expecting something that could test the limits of even their not-delicate sensibilities. But the truth is actually much more interesting: The film was banned because back in 1969 the Japanese were still rather sensitive about how handicapped and "malformed" people were portrayed in film in the wake of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, particularly when the characters are shown to be mentally unbalanced because of their deformities. While the film certainly has some disturbing content; touching on incest, mutilation and cannibalism; the story (which was pieced together from several stories by noted Japanese author Edogawa Rampo) is really a perverse mystery where all is revealed in the final ten minutes. It's the odd stylistic touches, particularly in the performance of Tatsumi Hijikata, that make this a special treat for fans of genre cinema.

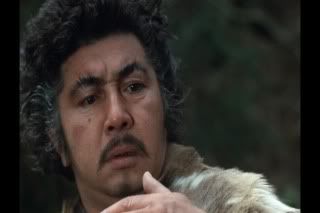

Teruo Yoshida plays Hirosuke Hitomi, a young doctor who finds himself imprisoned with no memories of his past besides flashes in his dreams of a weird figure dancing by the beach of a strange island. After accidentally murdering someone in self defense, Hitomi escapes only to discover his rather incredible resemblance to a local man who has just passed away. Hitomi decides to impersonate the dead man in the hope of learning about a possible connection to the island from his dreams. What he actually discovers is an island full of deformed and malformed men and women, led by a strange doctor (Tatsumi Hijikata) who may actually be his father. All will be revealed on the island, but will Hitomi and his associates ever be able to leave?

Teruo Yoshida plays Hirosuke Hitomi, a young doctor who finds himself imprisoned with no memories of his past besides flashes in his dreams of a weird figure dancing by the beach of a strange island. After accidentally murdering someone in self defense, Hitomi escapes only to discover his rather incredible resemblance to a local man who has just passed away. Hitomi decides to impersonate the dead man in the hope of learning about a possible connection to the island from his dreams. What he actually discovers is an island full of deformed and malformed men and women, led by a strange doctor (Tatsumi Hijikata) who may actually be his father. All will be revealed on the island, but will Hitomi and his associates ever be able to leave?

Ironically for a film about the ugliness of man, Horrors Of Malformed Men is an often intensely beautiful film, from the spastic dancing from Hijikata to the painted female figures that litter the island, this is a stylish and attractive film, particularly in the second half. Even the opening credits, filled with extreme close-ups of spiders feeding, is grotesquely beautiful. Director Ishii's career spanned multiple genres over his long career, including some Sonny Chiba action films, but while he could make populist entertainment he wasn't afraid to make some odd and interesting choices in his filmmaking.

But it's the Butoh dancing of Tatsumi Hijikata that I take away most from the film. Butoh is more a movement than a specific style of dance, and often typically involves playful and grotesque imagery, taboo topics, extreme or absurd environments. In this film the actor is first seen moving almost crab-like among the rocks of the island, and when Hitomi finally meets him his "dance of darkness" is exciting while remaining disturbing to witness. The following gutteral, shifting performance is quite amazing, even as we discover some horrifying secrets about the island and its inhabitants.

But it's the Butoh dancing of Tatsumi Hijikata that I take away most from the film. Butoh is more a movement than a specific style of dance, and often typically involves playful and grotesque imagery, taboo topics, extreme or absurd environments. In this film the actor is first seen moving almost crab-like among the rocks of the island, and when Hitomi finally meets him his "dance of darkness" is exciting while remaining disturbing to witness. The following gutteral, shifting performance is quite amazing, even as we discover some horrifying secrets about the island and its inhabitants.

Despite these unique and exciting elements, the film remains deeply flawed, particularly in its final ten minutes when Ishii feels the need to bring all of the elements - horror, mystery and tragedy- together. While the film is set up as a mystery from the beginning, with echoes of Hitchcock in its main character and his actions, I found myself losing interest in the whodunnit aspect of things by the time the cast made it to the island. Introducing a character who arrives to explain it all Scooby-Doo style undermines the tension significantly, and brings things to a rather abrupt halt. This scene is followed by a memorable but laughable scene that represents both the high and low point of the film.

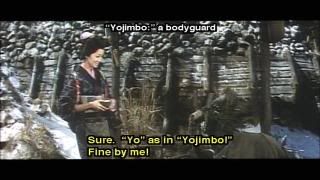

Whatever flaws the film may have, the same cannot be said for the wonderful DVD from Synapse Films. The movie is presented in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio and it looks pristine throughout, with sharp, mesmerizing colors. The film has clear and easy-to-read subtitles, a necessity in a movie that is designed to be dreamlike and confusing.

There are also some wonderful included extras which serve to put Horrors Of Malformed Men in the proper historical context while extrapolating on the history of Teruo Ishii and Edogawa Rampo. First we have a quiet, but intermittently fascinating, commentary from author Mark Schilling. I had to strain to hear the track at times, and there are long gaps of silence, but as someone who was instrumental in getting the film released it's still quite interesting to hear Schilling's perspective on the director's career.

More interesting is a featurette featuring brief interview segments with cult filmmakers Shinya Tsukamoto (Tetsuo: The Iron Man, Tokyo Fist) and Minoru Kawasaki (The Calamari Wrestler). Both men speak hightly of Ishii and his films, as well as the influence that the director has had on their own careers. Interspersed are tantalizing clips from some of Ishii's other films. Ishii in Italia is another short featurette following the director in 2003 at the Far East film festival in Udine, Italy. Clips of him introducing some of his films, including Malformed Men, are included. It's a breezy and fun segment showing a man that seemed very much alive just a few years before his death.

Finally, we also have a trailer for the film, a gallery of Ishii poster art, and brief biographies for Ishii and Edogawa Rampo.

Whatever flaws the film may have, the same cannot be said for the wonderful DVD from Synapse Films. The movie is presented in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio and it looks pristine throughout, with sharp, mesmerizing colors. The film has clear and easy-to-read subtitles, a necessity in a movie that is designed to be dreamlike and confusing.

There are also some wonderful included extras which serve to put Horrors Of Malformed Men in the proper historical context while extrapolating on the history of Teruo Ishii and Edogawa Rampo. First we have a quiet, but intermittently fascinating, commentary from author Mark Schilling. I had to strain to hear the track at times, and there are long gaps of silence, but as someone who was instrumental in getting the film released it's still quite interesting to hear Schilling's perspective on the director's career.

More interesting is a featurette featuring brief interview segments with cult filmmakers Shinya Tsukamoto (Tetsuo: The Iron Man, Tokyo Fist) and Minoru Kawasaki (The Calamari Wrestler). Both men speak hightly of Ishii and his films, as well as the influence that the director has had on their own careers. Interspersed are tantalizing clips from some of Ishii's other films. Ishii in Italia is another short featurette following the director in 2003 at the Far East film festival in Udine, Italy. Clips of him introducing some of his films, including Malformed Men, are included. It's a breezy and fun segment showing a man that seemed very much alive just a few years before his death.

Finally, we also have a trailer for the film, a gallery of Ishii poster art, and brief biographies for Ishii and Edogawa Rampo.

Despite my reservations about the film's ending, this is a wonderful DVD that serves to both show a fascinating, and unfairly maligned, film, as well as examine the works of a director who deserves greater exposure for his large catalogue of films. Horrors Of Malformed Men is a beautiful, eerie and haunting work that has obviously influenced a generation of Japanese film-makers (you can see echoes of the film in parts of The Ring and other contemporary Japanese horror films). A truly impressive work, and well worth adding to your collection.