Times are tough in the Japan of 1918. A shopkeeper and his wife, having just opened up a new store, require protection from Boss Onimasa, if their business is to survive. Unfortunately, they have no money to offer him. On the other hand, they have plenty of children. When Onimasa arrives, however, he is less impressed with the boy they offer him than he is with their daughter, Matsue. He takes them both, but only Matsue is strong enough to withstand estrangement from her family and the rigors of yakuza life. It is through Matsue’s eyes, then, that we witness the fall of Onimasa’s yakuza clan, and the tumultuous forces that shaped Japan from 1918 until the World War II.

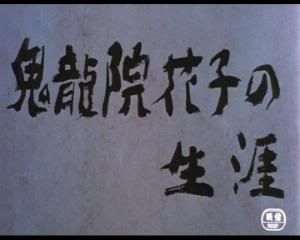

Hideo Gosha’s 13th film, and his first film of the 80s, sees the director producing one of his most humane and dramatic pieces. The narrative of the film centres around Matsue Kiriyuin (Masako Natsume), the adopted daughter of Boss Onimasa, and her quest to live the life she wants to lead despite being forced into the chauvinistic and violent world of the yakuza. That the film centers on a female lead marks a distinct departure for Gosha, one that seems to inaugurate the latter part of his career. Even though Goyokin, Tenchu!, and, to a certain extent, Hunter in the Dark all acted as a criticism of the hyper-masculine way of life that is intrinsic in the samurai or the yakuza (or the samurai and yakuza film), they all worked from within that system. In Onimasa, Matsue Kiriyuin is able to take more of an outsider’s view of the violent world she inhabits, and in doing so helps the viewer to see it as fraudulent, and often pathetic.

Though Matsue acts as the anchor of Onimasa's narrative, it is the titular character himself, played by Tatsuya Nakadai, who really drives the piece. After being all but absent from Tenchu! and harnessed with a fairly uninteresting character in Hunter in the Dark, Gosha finally brings Nakadai back into the spotlight, where he belongs. And Nakadai delivers. Generally a reserved actor, allowing his eyes or the pitch of his voice to carry the part, here Nakadai hams it up gloriously. His Onimasa is a weird, eccentric figure, who truly believes himself to be a samurai. It is almost impossible not to smile when he is on the screen. This makes it all the more shocking when he does truly reprehensible things, such as trying to rape his own adopted daughter. Its at moments like these that you suddenly remember that Onimasa isn’t just some entertaining old man--he’s a yakuza boss, and he didn’t gain that position by being all smiles and sunshine.

The plot is long and detailed (Onimasa clocks in at about 2.5 hours), and there’s too much to get into in a short review. The film follows Matsue’s life in the yakuza, from being a child acting as a server to becoming a fully grown woman who strives to leave her criminal family behind her. She succeeds in the life she is forced into through the power of her will. In one of the film’s funnier moments, Onimasa and Matsue, still a child, engage in a shouting match over whether or not she’ll be allowed to go to school. Onimasa, not surprisingly, doesn’t think that women should be educated; however, no matter how much of a hard ass Onimasa might be, he is unable to shout down a little girl as determined as Matsue, and in the next scene we see her attending classes. This sort of thing happens throughout the film, with Matsue always coming out on top.

The main conflict of the film--not the internal conflict of the family, but the one that leads to the bloody finale--occurs due to Onimasa's belief that he is not a yakuza, but a samurai. After he is ordered by the big boss (Tetsuro Tamba) to put down a strike, Onimasa is convinced by the union heads that a real samurai would help the people, and not those in power. Onimasa is convinced, and in helping the union he finds his clan ousted from the greater yakuza organization. Onimasa's decision would be admirable, if it weren't for the fact that he doesn't even understand how he got into it.

Onimasa is not an action movie, even though it does contain moments of graphic violence (it should be mentioned, here, that the film contains a rather violent dog fight that certainly seems authentic, and will probably make some viewers uncomfortable). The film is, on the other hand, a rather effective period piece. Through the eyes of Matsue Kiriyuin we get to see the decline of the yakuza and the great Onimasa clan. As well, we get to see the changing Japanese society, with a special focus on the government’s actions against the perceived Communist threat. The lack of action might disappoint fans of Gosha, which is too bad, since Onimasa shows the director at the height of his power. Every shot in the film seems perfectly composed, and the acting--especially from Nakadai and Natsume--is great on all fronts. It also contains a great performance by Shima Iwashita in the role of Onimasa’s wife, a no-bullshit lady who really holds her own in scenes with Nakadai. Add to that an appearance by a moustachioed Tetsuro Tamba and you’ve got quite the ensemble cast.

Onimasa can also be seen as playing with the audience’s expectations of yakuza films. Generally speaking, the yakuza films of the 60s portrayed the yakuza as the last bastion of the samurai way of life, with honourable yakuza (often Ken Takakura) overcoming corrupt yakuza and city officials to help the common man. The yakuza films of the 70s--notably those directed by Kinji Fukasaku--showed the yakuza in a grimmer light, portraying them as common criminals. Onimasa, completed in the 80s, seems to play off of both of these ideas. Onimasa considers himself a samurai, and tries to fight for the common man, but his fixation on bushido seems more delusional than noble, and is often shown to be only skin deep. In the end, the yakuza--at least the sensible ones--are the criminals that Fukasaku showed them to be, and people like Onimasa are mere fictions.

Like so many of Gosha’s films, Onimasa is sadly unavailable in North America. Wild Realm films has released a beautiful edition, and I’m hopeful that someone will port the film over for a R1 release. The French are simply years ahead of us in samurai and yakuza films. For you French-speaking types, the disc contains an interview with Hideo Gosha, the film’s trailer, photos from the film, and a Gosha filmography. It really is a great package--too bad there’s no English subtitles.

Onimasa is one of the few films in recent memory that surprised me. A rather unheralded Gosha film in North America, I was expecting a fairly unremarkable and dull yakuza film. Instead, it seems Gosha produced a drama whose quality could match that of his action films of the 60s and 70s. Maybe the film isn’t for everyone, but fans of yakuza films, Hideo Gosha, or Tatsuya Nakadai would be crazy to pass it up if the opportunity arises.

No comments:

Post a Comment