PLOT:

When a mountain man (Lone Wolf and Cub’s Tomisaburo Wakayama) kills a man and steals his wife (Shima Iwashita), he bites off more than he can chew. Rather than being a submissive victim, the beautiful woman soon browbeats her murderous husband into total compliance, convincing him to murder all but one member of his harem of dirty mountain women. She soon becomes his wife, and convinces him to take her (and the one girl she spared, now a maid) to the capital, where the mountain man begins his new vocation: collecting heads for his wife, who uses them as props in her own personal melodramas. Soon, Wakayama (his character has no name) becomes a feared figure in the city, and his wife’s collection of heads grows and grows. But how long can it last?

REVIEW:

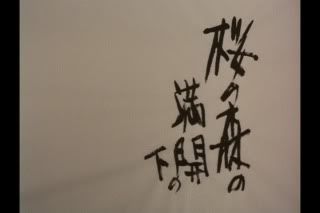

Beauty and horror combine in equal measures in this mid-70s outing by Masahiro Shinoda. Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees begins with gorgeous images of cherry trees (you guessed it, blossoming) in a modern landscape. As people go about their day, and young voice tells us that it was once believed that those who walked under the blossoming cherry trees would lose their minds. And with that brief prelude, the film takes us back, into the past, where Wakayama attacks an entourage and takes by force the woman who will be his wife.

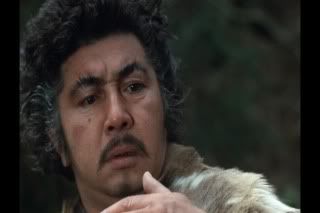

You can’t help but feel sorry for Wakayama, despite the fact that he plays a wild, unkempt, and murderous mountain man. In fact, there’s something cute about his rustic life, his shaggy looks, and the way his stocky little body sprints around the forest, causing mayhem. It’s a clear example of a bad character being made to look good by the presence of a truly evil character--in this case, his wife.

You know Wakayama is in for it almost immediately: when he tells his new wife that he’s abducting her, and taking her to his home, she makes him carry her. Surely, if he’s such a tough man, he can carry his wife up a mountain, right? And Wakayama, eager to show off his manliness, does just this, even though it entirely exhausts him. When he gets to his hovel, he introduces his new wife to six or seven others, which he’d probably accumulated in much the same way he got this new one. She asks him to kill them--all but one, to be her maid--and he does so. The mountain man clearly represents a sort of bestial, alpha male badness, but she represents something else altogether. Soon she henpecks him out of his comfort zone, forcing him to move to the capital. And then he is murdering for her, cutting off people’s heads so that his wife can put on bizarre, pornographic plays, with them as props.

Of only three main characters (the mountain man, his wife, and the maid), two are women, and they are both given strong, important roles. The maid, who has a crippled leg, is gentle, and acquiescent. She never complains, no matter how bizarre her new mistress is, and even though her sister-wives have recently been put to the sword by her former “husband.” But she is easily overshadowed by the wife, who is one of the most evil women in cinema.

And it’s worth commenting on her as an “evil woman,” and not just a woman who is evil, since her evil is directly tied to her gender. She entrances the mountain man with her beauty, and it is only by questioning his masculinity (and therefore acting as a woman questioning his status as a man). Once she begins collecting severed heads, it isn’t long before she incorporates them into her sex life, using them for all sorts of sexual degradations. It is her status as a woman--a beautiful, soul-sucking woman--that allows her to manipulate Wakayama as she does. So evil is she, it has to be wondered whether she’s a human at all.

Perhaps the wife is some sort of demon, or hungry ghost. It’s certainly a possibility. She seems strangely detached from the rest of the world--though she longs to leave his mountain cabin, when the mountain man takes her to the city, she remains indoors, hidden away with her grisly toys. Only the maid sees her, and perhaps her ready compliance to her mistress’s wants speaks to her awareness of her lady’s evil nature. Certainly this touch of the supernatural would not be out of place in a film where falling cherry blossoms are shown to drive people completely and utterly mad. And it is this madness, this mindless insanity, that the mountain man begins to crave, perhaps as the only escape from the trap that his wife has left him in.

2 comments:

Your comments about the wife are pretty interesting.

I'm surprised it's taken so long to dawn on me, but I've noted in several films (including 2LDK and Audition, and arguably half of the onryo movie's I've seen) that the "evil female" seems to be a regular villainous archaetype in Japanese cinema.

No wonder Kurasawa had no problem adopting Macbeth. :)

Cultural misogyny manifesting itself, perhaps? Or just an accepted artistic archaetype in general?

Cool post! Thanks for sharing.

Post a Comment