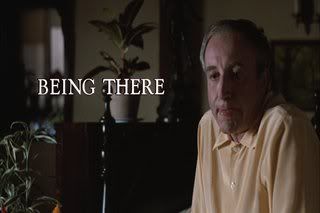

PLOT:

Hal Ashby's 1979 masterpiece Being There stars comedy legend Peter Sellers in his finest hour. Chance (Sellers), a simple-minded and TV-addicted gardener, has been living and working on the property of a wealthy old man in Washington D.C. for as long as he can remember. When the old man passes away, Chance is thrust into the real world--a place he seems hardly suited to survive in. Within a few hours, though, a lucky accident introduces him to Eve Rand (Shirley MacLaine), wife of the wealthy and powerful industrialist Ben Rand (Melvyn Douglas). The Rands are quite charmed by Chance, and take each of the inane and dim-witted things he says as gems of Zen-like wisdom. Because he is white and well-dressed, they assume that he's a gentlemen of property, a professional. Oblivious to all of this, Chance soon finds himself a confidant to Mr. Rand, a TV celebrity, an adviser to the President of the United States, and a potential lover to Eve.

REVIEW:

Chance watches television, all the time, every day. This is not because he is a member of the younger generation; on the contrary, it’s the 60s, and he’s already old. No, Chance watches so much television because he is so empty inside. There is nothing to him, only surface. It’s as though, in watching TV, he can momentarily fill himself up with the flashing images and inane chatter. It's his only teacher.

It's fitting that, when Chance finally leaves the house of his employer, entering the world for seemingly the first time, a revised version of the 2001: A Space Odyssey theme starts playing. This is, indeed, an epic journey for the simple gardener, no less life-changing than Dave's journey to--well, whatever happens in 2001.

I think that one of the reasons the Rands accept Chance as one of their own--mistaking his name, "Chance the gardener" as "Chauncey Gardiner"--is that Chance himself would never think negatively of anyone else. His perspective effects others. But of course, that's not the main reason for the confusion. Louise, the African-American maid who used to work with Chance at the old man's residence, spells it out pretty clearly:

"It's for sure a white man's world in America. Look here: I raised that boy since he was the size of a piss-ant. And I'll say right now, he never learned to read and write. No, sir. Had no brains at all. Was stuffed with rice pudding between th' ears. Shortchanged by the Lord, and dumb as a jackass. Look at him now! Yes, sir, all you've gotta be is white in America, to get whatever you want. Gobbledy-gook!"

Visually, one thing I found striking about Being There was how much of the background was let in to each shot. It seems to me, in today's Hollywood, that films are shot almost entirely in close-up, and instead of close-ups we get extreme close-ups. Being There is filled with master shots, with scenes composed so that the true size and weight of the Rand's mansion is felt by the viewer. It helps to evoke the wealth of the Rands, and it helps to show how small each individual is when compared to his or her surroundings. On a more psychological level, it helps situate Being There in the real world. This isn't the comedic world that so many films inhabit nowadays, where the insane antics of the main characters are somehow normalized; this is the real world, and so the jokes resonate on a different, deeper level, even if they aren't the laugh-out-loud howlers you might expect in today's comedies.

As a comedy, Being There is, essentially, a one-joke movie. Chance is an imbecile, but everything he says is accepted as wisdom. The laughs come from seeing how each of his simple-minded observations are taken as stunning and honest insights, how people bend over backwards to accept Chance as brilliant and profound. It should be repetitive and dull. But it isn’t. It speaks something to the brilliance Sellers and the craft of the screenplay that Being There never overstays its welcome, and even on repeated viewings it always seems fresh.

Chance sees the world with a fresh perspective, with new eyes. People see him the same way, unable to accurately place him. He accepts people at face value, and expects the best of them, unable to think otherwise, and his outlook seems to have a reciprocal effect. After becoming immersed in the film, something miraculous happens: the viewer begins to see things the way Chance sees things--simplistically, honestly, without judgment. You are not just watching the film, but seeing it (and the people in it) a new way. You see Benjamin Rand and the President of the United States as people, as humans, rather than as the roles they fill. That they are wealthy, powerful white men--ruthless capitalists, part of the machine--becomes secondary, and their existence as people, just people, comes to the forefront.

We’re supposed to laugh, at the idiocy of Chance, at how people accept his words without question, with a critical response. But the last time I watched Being There, I couldn’t help but think: what if he isn’t stupid? What if he is professing wisdom, and giving it out honestly, and freely, without a thought of himself? What if Chance is some modern-day Buddha, providing enlightenment to those who will listen? The evidence is there, after all.

The recently released and hilariously-titled “Deluxe Edition” of this fine film is a bare-bones affair with the following special features: Memories from Being There with Ileana Douglas. That’s right, the granddaughter of Melvyn Douglas vaguely recalls some stuff about the filming of the movie, which took place when she was 14. Great. But it doesn’t matter, because Being There is one of the best films of the 70s, or any decade, and you should own it.

No comments:

Post a Comment