Tuesday, November 30, 2010

Capsule Review: The Hangover (2009)

Saturday, November 27, 2010

Saw IV, V and VI: Political Torture and The Saw Legacy

In my previous look at the Saw phenomenon - covering the first three films - I mentioned a personal fascination with film series' that go long, and the evolution that begins to occur within. I mused about some of the possibilities of how the Saw series might progress, possibly through introducing more humor (which may be welcome considering how deadly serious the series had been), or perhaps introducing a note of meta-commentary as a way of examining the omnipresence of the series as a whole. While the first point certainly never revealed itself - the only humor ever present is the sheer disbelief at the complexity of some of the murder devices - there is a touch of the second point in the series' 6th installment, which introduces a few "ripped from the headlines" elements regarding insurance companies and housing loan scams that were particularly topical at the time the film was made.

One element of the series that had already started to develop in the first three films, and certainly continued throughout the next three, was the progression of Jigsaw/John Kramer as a sort of sympathetic anti-hero. While his methods are obviously brutal, since the death of character in Saw III the films have begun filling in his back-story and revealing the demented, but concrete, method behind his madness. This softening - if you can call it that - is obviously intentional, and shows a recognition that Kramer (and Tobin Bell's continually terrific performance) are what the fans come to see. It also reflects a similar evolution to that which occurred in the Friday the 13th series, where many of the victims were introduced as despicable and unlikeable characters, so the crowd would get more satisfaction from their eventual gory deaths. Slasher films, somewhat incongruously, are often very puritanical, with excessive sexuality and drug use being punished by death. The crimes of the victims in the Saw series tend to be a little more complicated, but the idea has begun to be the same - while we develop an emotional connection, we're always at a distance thanks to their eventually revealed despicable behavior.

However, the common criticism involving the near comical levels of complexity regarding the death devices in the series has been replaced with the disbelief at the sheer level of back-story that has been able to be filled in. While the creators have been smart to - even peripherally - keep Jigsaw at the forefront of the films, it seems that there would have to be limits to what audiences would accept as elements that can be continually filled in. The web of events being weaved remains interesting, and I respect the filmmakers for taking small details from previous films and tying them into the greater picture, but by the end of this second trilogy of films it seems we've nearly reached the limit of this sort of retroactive

continuity.

I will admit that the details of the individual films tend to run together in Saw IV, V and VI, as the muddle of flashbacks and "shock" reveals begin to take their toll. It also seems that we've passed the point of no return regarding the level of violence in these films - as the comparative restraint of the first two films has given way to an expectation of bloodshed that actually serves to reduce much of the film's suspense. If there's a device that is meant to mutilate someone, the filmmakers will inevitably be showing you the evisceration in grand detail - at least in some capacity. Anyone who has watched up to this point already realizes that nobody escapes unscathed, which is just how the audiences seem to like it.

Saw IV (2007) finds the series at a crossroads, though also finds the return of many of the players from the previous film - including director Darren Lynn Bousman (who helmed the previous two installments). The film's central and most interesting character is now dead, and since the film doesn't trade on supernatural elements, we're shown John Kramer's autopsy in revolting (though, I have to admit, fascinating) detail. However, Kramer/Jigsaw was plenty busy before his death recording seemingly dozens of tapes to make sure everyone tangentially related to his life would be affected in some way. Much of the running time is devoted to Lieutenant Rigg (Lyriq Bent), who - after finding the body of Detective Kerry from the previous film - finds himself obsessed with finding Eric Matthews (Donnie Wahlberg's character from the previous two films) to the point where he's sent home to recuperate mentally. Jigsaw - however - has taken this opportunity to run the officer through a series of different tests meant to challenge his obsessive behavior.

We're also introduced to FBI agents Peter Strahm (Scott Patterson) and Lindsey Perez (Athena Karkanis), who are diligently searching for clues regarding the fate of Jigsaw, while also attempting to track down the whereabouts of Riggs. They are assisted by Detective Hoffman (Costas Mandylor), who soon finds himself part of one of Jigsaw's trademark devices - also involving Matthews.

Got all that? The cast of characters has started to pile up - and I didn't even mention the increased presence of Kramer's wife Jill Tuck or the appearance of previous protagonist Jeff Denlon - but the real fascination here comes from the increased number of flashbacks to Kramer's pre-Jigsaw life. I usually get annoyed by such attempts at humanization, but Bell's performance is so subdued and strong that he's able to make these moments - involving his relationship with Jill and her eventual miscarriage - really carry some weight. Rigg's journey is less interesting, and serves mostly as a catalyst for the film's trademark "games" - which seem a little less imaginative than usual. I found the film's ending to be rather anticlimactic, though it seems to represent a rather obvious (and necessary) changing of the guard concerning the direction of the series. The final reveal - another series trademark - is quite effective, and sets the next film up nicely.

Saw V (2008) marks a minor change in direction for the series, as we now have a new antagonist who has shown to have existed in the background of all of the previous films. We also have a terrific beginning which shows Agent Strahm managing to save his own life by giving himself a tracheotomy with a pen (after finding himself trapped in what appeared to be Radiohead's "No Surprises" video). Unfortunately, the rest of the film isn't nearly as interesting, despite a new director (Saw series production designer David Hackel) and some memorably gory moments (particularly the Pit and the Pendulum-inspired pre-credits sequence).

Once again the flashbacks tend to be the most interesting part, as we see the apprentice's involvement in some of the more memorable moments of the previous films, as well as the beginnings of his relationship with the Jigsaw character. The big murder set pieces come from a central game featuring five new victims whose selfishness has indirectly led to the deaths of eight people. I mentioned in the previous article about the film's central premise bringing to mind the Vincenzo Natali's Cube, and the dynamic of that film is particularly evident in the series of tests experienced by the characters here. However, they are a prime example of the sort of barely sympathetic characters that the series now specializes in as cannon fodder for the distinctive traps.

The acting in the film is solid across the board - only the first Saw film has particularly egregious examples of bad performances - though I found myself totally unable to care about the Peter Strahm character and part of that is due to the hard-nosed performance of Scott Patterson. We discover later that Strahm is being set up as a possible suspect for the post-Jigsaw murders, but while this may explain why they don't properly develop his character it doesn't make for very interesting viewing. We also get one of the least interesting climaxes of the series, making this likely the weakest entry as a whole in the series up to this point.

Saw VI (2009) somewhat surprisingly proved to be a return to form thanks to a combination of factors, not the least of which was the decision to embrace the thematic elements that supporters of modern splatter had always suggested were evident - the reflection of real world concerns. While I wrote in the previous article about the dubious suggestion that the acceptance of real world torture in times of war was a motivating influence on the development of the "torture porn" genre, the choice to incorporate references to the mortgage crisis in the guise of the predatory lenders in the pre-credit sequence and the much more overt references to the loathsome practices of Insurance companies as related to the recent American health care debate give the film - which has a comparatively short production schedule - a real sense of timeliness.

It also serves to continue the trend of the last few films of softening the impact and tension of the various trials and games being presented by having those being tested be quite unsympathetic. With most of the supporting cast having been dispatched, we're left with a much more focused plot of watching Jigsaw's apprentice slowly get revealed thanks to some past sloppiness, as well as a series of brutal games being played by health insurance executive William Easton (Peter Outerbridge) - who became a target of Jigsaw after earlier turning down John Kramer's attempts to get experimental treatment for his cancer. There are some fairly big reveals throughout, and I was impressed by the complicated ending which serves to quite effectively bring the numerous disparate threads together.

Editor for all of the previous films in the series, director Kevin Greutert doesn't provide the flashy transitions of Darren Lynn Bousman, but does a good job of tying this stage of the storyline together, while leaving a few strands for whoever is called on to follow (which ended up being himself, since he's also the director of 2010's Saw 3D). While I mentioned that Easton's character made his eventual fate less than distressing due to his dubious morality, Outerbridge does a wonderful job of balancing his expected smarm and smugness (in the flashbacks) with his obvious desperation once trapped. Tobin Bell gets to show off a bit more emotion as well in his few scenes, though the series as a whole is starting to stagger with the weight of the new back-story being piled upon it.

Even now going into the seventh and (not likely) final film in the series, I can certainly appreciate the appeal of Jigsaw as a villain - who holds quite strongly to a particular personal moral code, despite putting the characters in these films through absolute agony. He quite quickly replaced the various antagonists as the heart and soul of this series, but by killing him off in the third film the filmmakers have presented themselves with quite a quandary - keep moving deeper into a back-story that is already starting to get ridiculous, or try and present a new set of players? While some of the creative forces in this series have bent the formula slightly, there must be a very real concern about tipping the apple-cart, though the success of the most recent film does show that this series still has potential - or at least there's still an audience for bleak and cynical bloodshed.

I plan on completing my view of this series with a final look at the most recent and possible final entry in the series, in which perhaps the creators will answer some of these concerns.

filmsquish.com 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die Blog Club

In conjunction with the 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die project on this site, we're happy to be involved with the (re)launch of the 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die Blog Club taking place at filmsquish.com. Look for more full length reviews of classic films, and check out filmsquish for plenty of alternate takes weekly.

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

The Politics of the Walking Dead

This comes from a person who has all but given up on television thanks to the plague of reality television.

Heh. An apt analogy given the topic of discussion.. Anyway.

Thanks to the masterful storyline of AMC's newest masterpiece, the politics of the zombie are once again en vogue and the zombie once again takes its rightful place in the hallowed halls of proper scholarly discussion.

Don't laugh. I'm being serious!

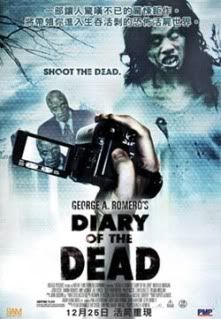

To put it bluntly, George Romero is the horror genre's own Mark Twain and Night of the Living Dead isn't so much about zombies as it is a scathing indictment of society at large.

In order to understand the basis of Romero's critique, you have to ask yourself one important question: What is it about zombies that scares the hell out of you?

Let's examine what makes zombies tick... so to speak....

Zombies represent the very worst incarnation of social conformity as well as the complete destruction of individualism and self-determination. The people in life who you once loved or respected are replaced with rotting shells whose single motivation is the overwhelming need to eat you alive.

After you die (provided that there is enough of you left to re-animate), you will rise up and join them in their task until every last living person is wiped off of the face of the earth.

The [REC] films put an interesting spin on this idea. Over the course of the movies, the audience eventually discovers that the zombies are not so much zombies in the traditional Romero sense as they are terrestrial extensions of a malevolent supernatural force.

Being "dead" in the [REC] movies not only means that you lose your free will; it also means that you lose your immortal soul.

Zombies don't eat because they are hungry; they eat for the sake of eating. Furthermore, unless zombies are in pursuit of a meal, they are content to meander about in the well documented shambling gait.

In short, zombies are the epitome of two of the Seven Deadly Sins; those being Sloth and Gluttony. It is no accident that Romero chose the zombie as the vehicle to criticize American society about its wanton fascination with consumerism.

Society's need to "have" is just as destructive to the body politic as the zombie's need to "eat." Neither impulse is driven by natural behavior and the satisfaction of that impulse usually takes a decidedly violent form.

If humans don't get what they want, they take it...

So do zombies... and both parties do this without consideration for supply.

Whether it be brains, cheeseburgers, or crude oil, the primary preoccupation of both human and zombie societies appears to be not only to take until there is nothing left; it is also to take without leaving something of value in return.

Whomever dies with the most toys wins and whomever is undead and eats the most brains wins.... sort of...

Romero's shopworn criticism of rampant consumerism is further coupled with a scalding critique of materialism and suburban flight in the 1978 sequel, Dawn of the Dead.

There is a specific reason why the primary set piece of this film is a shopping mall. Poor Zack Snyder did not figure that part out in his 2004 remake. Next time you watch the remake, listen very closely and you just may catch the sound of the "whoosh" of the principles of the first film sailing over his head.

Despite the ever present hordes of brain-sucking shufflers, the zombie itself is only part of the zombie film equation.

And before you ask the question, my answer is "no." Zombies are not supposed to run.

The sensation of dread you feel during zombie movie chases comes from the awful realization that you are outnumbered.

Zombies don't have to chase after you because there is nowhere for you to hide. Their numbers will infest every nook and cranny in the world. The world doesn't belong to you anymore; it belongs to the shamblers and eventually they will find you.

They won't discover where you are because they are actively looking for you. They will find you simply because there will be no place on earth where they will not be present, and they will always be on the hunt because they will never rest.

Consequently, if you are a zombie at the time when the zombie apocalypse goes down, then your worries are usually over. The real story of any good zombie movie deals with how the death and undeath of civilization affects the survivors.

The tragic conclusion of Night of the Living Dead is nigh-legendary in the halls of horror cinema. The brave African American protagonist, Ben (Duane Jones), manages to survive the zombie onslaught only to be mistaken for a ghoul by a posse of rednecks, shot dead, and subsequently thrown onto a burning pyre.

In Dawn of the Dead, a biker gang shows up to the shopping mall to loot the stores and manages to become just as big of a menace to the survivors inside the mall as the zombies lurking outside.

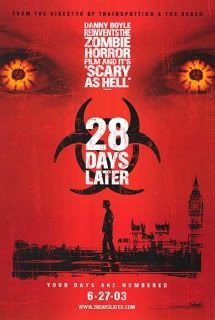

28 Days Later (Come on now. It's a zombie movie when you think about it...) showcases a unit of psychotic British soldiers determined not only to outlast the infected hordes, but they also intend to repopulate the UK via a system of female sexual servitude.

Even, the survivors of the Day After in The Walking Dead painfully begin to realize that zombies are just another ornament on the Tree of Woe, as the series (in the true Romero-style edutainment spirit) tackles every socio-political hot button issue from racism (just like Night of the Living Dead did!) to spousal abuse.

Whether living or dead, the human monster is the most dangerous one of all.

The discussions that these films generate, tragically enough, are timeless debates because the social inequalities that they address are as present as they ever were, and we should have these discussions while we still have time.

The cautionary moral of the zombie fable is that one morning when we least expect it, the last grain of sand in mankind's hourglass will fall and social divides will no longer be defined by have and have-not.

On one side, there will be the quick and on the other side.. there will be the dead..

On that advent of the undead armageddon, all men will find themselves on equal footing... whether they like it or not....

Free at last....

Free at last....

Monday, November 22, 2010

Saw I, II and III and the Art of Torture: A Retrospective

Monday, November 15, 2010

Capsule Review: Blackmail (1929)

Saturday, November 13, 2010

Capsule Review: Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Capsule Review: Bus 174 (2002)

Capsule Review: Anvil! The Story of Anvil (2008)

Rock and Roll has provided great material for documentaries for decades, but the elements that make up these documentaries have been examined and parodied so often that it’s difficult to take a lot of the manufactured conflict and resolution seriously. But just when you think the genre has been tapped for all it’s worth – I felt that way after the Metallica documentary Some Kind of Monster – a film like this comes along to give you a bit of faith in the redemptive power of rock music. Presented as sort of a real life This Is Spinal Tap (some of the interview segments are obviously supposed to bring that film to mind, and there are memorable shots of an amplifier going to 11, as well as the requisite trip to Japan), the film follows Canadian 80s metal band Anvil as they attempt one more shot at the fame they had 20 years earlier when they shared the stage with luminaries like Scorpions and Bon Jovi. Sometimes depressing, often hilarious, we get a backstage pass for a disastrous European tour, in-fighting (between original members Steve "Lips" Kudlow and drummer Robb Reiner) and attempts to record and market their 13th album This Is Thirteen. It doesn’t take a love (or even like) of heavy metal music to enjoy the rare insight into the struggles of two men desperate to keep doing the thing that they love, even as musical trends and their own bodies seem to be working against them.

Rock and Roll has provided great material for documentaries for decades, but the elements that make up these documentaries have been examined and parodied so often that it’s difficult to take a lot of the manufactured conflict and resolution seriously. But just when you think the genre has been tapped for all it’s worth – I felt that way after the Metallica documentary Some Kind of Monster – a film like this comes along to give you a bit of faith in the redemptive power of rock music. Presented as sort of a real life This Is Spinal Tap (some of the interview segments are obviously supposed to bring that film to mind, and there are memorable shots of an amplifier going to 11, as well as the requisite trip to Japan), the film follows Canadian 80s metal band Anvil as they attempt one more shot at the fame they had 20 years earlier when they shared the stage with luminaries like Scorpions and Bon Jovi. Sometimes depressing, often hilarious, we get a backstage pass for a disastrous European tour, in-fighting (between original members Steve "Lips" Kudlow and drummer Robb Reiner) and attempts to record and market their 13th album This Is Thirteen. It doesn’t take a love (or even like) of heavy metal music to enjoy the rare insight into the struggles of two men desperate to keep doing the thing that they love, even as musical trends and their own bodies seem to be working against them.

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Capsule Review: Paranormal Activity (2007)

Sunday, November 7, 2010

The Green Slime (1968)

This is a rather big cheat, as though i'm writing this for the Wildgrounds Japanese Blogathon it's actually an international production - though co-produced by Toei Company and lensed in Japan - with an entirely English speaking cast. That said, it was directed by the late, great Kinji Fukasaku (who had a long career directing genre films, but might be best known for helming Battle Royale) and features plenty of miniature special effects by Toei's usual Godzilla film crew, so i'm thinking it should still count. Add in the fact that The Green Slime has just been released in beautiful widescreen through the great folks at the Warner-Archive and I don't think the timing could be much better. Considering how long the film has only been available in muddy, painfully cropped VHS versions, this new version is practically a revelation.

Which isn't to say that this film is sterling. Even compared to the rough approximation of science expected in sci-fi films of the time, this one will consistently be having you scratch your heads. Despite coming out the same year as 2001: A Space Odyssey, the special effects in The Green Slime are more than a little rough around the edges, though have plenty of goofy charm. When you see a space station burning in space, sending smoke spiraling upwards you sort of just have to go with it. Combine with performances that run the gamut from stiff to uptight, and settings that represent that special 1960s view of the future (go-go boots, miniskirts and lots of flashing lights) and you're in for a very specific kind of pleasure.

It's the future and Commander Jack Rankin (Robert Horton) is pulled out of his impending retirement when some brainy science people at the United Nations Space Command discover an asteroid headed towards planet earth. Jack is plenty conflicted about his past - particularly his former friendship with Commander Vince Elliott (Richard Jaeckel from The Dirty Dozen) - but accepts the (apparently suicide) mission to plant charges on the asteroid, despite having to prepare for the mission on space station Gamma-3, which is currently Commanded by.. Vince Elliott. Are you getting all of this?

To make things even more complicated, Vince's current fiancée is Dr. Lisa Benson who used to be Jack's gal and still has rather obvious feelings for him, much to the perpetually intense Vince's chagrin. Despite the hard feelings, Vince volunteers to join the mission and the group successfully carry out their mission thanks to some heroics from Rankin. However, the scientist guy they brought along found a green slimy life form on the planet, and accidentally brought some of it back with him. You may be wondering if this slime feeds off electricity and rapidly grow into tentacled creatures that run amuck around the space station, and your suspicions would be correct.

Despite in-fighting, Jack and Vince decide to corral the creatures - who have the ability to heal themselves and procreate from a drop of blood - into a section of the space station and blow it up real good. When this proves only to litter the side of Gamma-3 with the creatures - realized in one of the film's crummier effects - Rankin makes the decision to evacuate the space station before demolishing the whole thing. There are lots of rubber suits, heroic sacrifices, and plenty of the titular green slime to go around.

Friday, November 5, 2010

Fish Story (2009)

The blurb on the back of the DVD cover reads: "FISH STORY weaves together several seemingly separate storylines taking place at different points in time over a 37-year span to explain how a little punk rock song can save the world." That's an intriguing premise, for sure. Can a song save the world? If you're going into this film, you're probably thinking, "yes, yes it can," since it's unlikely that someone will make a film about how a song can't save the world. And you'd be right.

What's perhaps quite surprising is the way that the song--performed by Gekirin (Wrath) and entitled "Fish Story"--manages to pull off this particular bit of salvation. This isn't a metaphoric or poetic saving of the world; people don't get together to sing it, fighting back injustice, oppression, etc., in the face of adversity. No, "Fish Story," the song, manages to directly influence events in just such a way that Earth's inevitable demise is staved off. Thank god for that.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. FISH STORY begins in 2012, with a comet hurdling towards Earth. This isn't the same premise as ARMAGEDDON--this is a deliberate ripoff of ARMAGEDDON. Even the plan to save the world is similar. In any event, instead of worrying about the future, one young man decides to go to the record store, and pick up an old album, which features--you guessed it!--"Fish Story." And so the tale of that song begins to unfold...

First we travel back to 1982, where a shy and submissive young'un named Masahi is introduced to "Fish Story" by his incredibly annoying and abusive 'friends.' Masahi (Gaku Hamada), chauffeuring his friends to a rendezvous, overhears that "Fish Story" is haunted; indeed, it has 60 seconds of silence, right in the middle of the track. The tape (remember, this is the 80s) warns that this isn't an error--the silence is deliberately there. But, his friend explains, some people don't hear silence. Some hear a woman screaming! And if you happen to be that someone, well, watch out, cuz your days are numbered. Not only is this a great urban legend, but it sounds exactly like the plot of so many recent J-horrors.

So, what happens to Masahi? Unfortunately, this is one of those films where, to explain it, I'd essentially be ruining the ending. You're not provided with the end of Masahi's story, before we time-travel to 2009, and a mini action movie/love story set on a boat, with a hero who has been specially trained (since birth) to fuck dudes up. Kind of like Steven Seagal's UNDER SEIGE. But not as good. And then--whiz, bang--we're back in 1975, to see how "Fish Story" was recorded in the first place. All the while, we keep checking back in to 2012, where--you guessed it!--a group of international astronauts have hatched a scheme to explode that naughty comet. Way to go, fellas!

Far and away the strongest part of the film is the final, oldest story: the 1975 genesis of the song that the whole movie revolves around. The actors are believable as a band, and not only a band, but a punk rock band. And that's hard to pull off; an actor with some ratty clothes and funny hair usually just looks like a fucking poser. More to the point, the actual song, "Fish Story," is an incredibly catchy piece of punk rock.

As you can probably tell, none of the individual sections of the movie provide the viewer with anything new. The journey of a submissive guy growing a pair, a hostage-taking and ass-kicking scenario, an unpopular band fighting to find its voice, a doomed planet--this is all tried and true stuff. Yoshihiro Nakamura's FISH STORY succeeds above all odds, because somehow it does make it all work. But you have to wait until the very last moment of the film. Until then, everything just kind of hangs there, tenuously. The film isn't helped by the fact that it, like a few recent Japanese films I've encountered (I'm thinking of LOVE EXPOSURE) looks like it was shot on the cheap, for a local cable channel. OK, that's probably an exaggeration; the best I can say is that the film itself doesn't look cinematic. It looks more like a soap opera. Still, FISH STORY tells a good yarn; like its namesake, a very regular tale (the story of a song) becomes bigger. And bigger. And bigger...

Dororo (2007)

Tezuka-san's stories have followed me all of my life and I am a better person for it. As I child and later as a teenager, I yearned for respect much like Kimba the White Lion and as a father I have pondered the mistakes of Professor Tenma from Astro Boy and have learned the true value of fatherhood and will always appreciate the blessings that come with raising a child.

In 2006, I heard that Dororo was going to be made into a feature length film. That bothered me because I wasn't terribly sure how well Tezuka would translate into live-action. The animated versions of Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion were entertaining enough kiddie fare, but they really weren't allowed to explore the depths that Tezuka did in the manga.

As a motion picture, Dororo has quite a bit going for it but it suffers from some of the same issues that Blood: The Last Vampire did.

The tale begins in feudal Japan with the warlord Kagemitsu Daigo (Kiichi Nakai) suffering a horrible military defeat. Kagemitsu seeks shelter in a remote temple and in his rage and despair, makes a pact with 48 evil spirits. He agrees to give each spirit (referred to as a demon in the English subtitles but more in flavor with the yōkai of traditional folklore than the demonic oni) permission to take one of the body parts of his unborn son in exchange for dominion over his enemies.

As a result, Kagemitsu's son is born with no limbs or facial features to speak of. In despair, Kagemitsu's wife sets their child adrift along a river in a style befitting Moses of Old Testament fame and the child is eventually plucked from the jaws of death by Dr. Honma (Yoshio Harada, whom some will recognize from Rônin-gai and the Christopher Lambert ninja vehicle, The Hunted).

Honma is no ordinary doctor; he specializes in alchemy and in yet another Tezuka plot device inspired by Frankenstein, Honma roams the country side and collects the dead bodies of children butchered in village raids during Kagemitsu's return to power. Honma then distills the corpses and uses the essence to create prosthetic devices that will allow Kagemitsu's heir apparent to function as a normal human being.

But Honma doesn't stop there. His final procedure gives the child use of a pair of magical swords grafted to his forearms and hidden away by his prosthetic hands. Eventually, the yōkai track the child down and kill Dr. Honma while trying to eliminate Kagemitsu's heir and then the story begins in earnest as Kagemitsu's heir (who eventually earns the name "Hyakkimaru" and is played by heartthrob, Satoshi Tsumabuki) embarks on a quest to kill the 48 yōkai and regain his lost humanity.

The hitch being that every time Hyakkimaru kills a yōkai, part of him returns to flesh and blood. As he regains his humanity, Hyakkimaru loses the invulnerability and preternatural ability afforded to him by his magical prosthetics.

If you're thinking, "So it is like a jidai-geki version of Edward Scissorhands," you would not be too far off of the mark.

The titular "Dororo" (Kou Shibasaki) is a tough yet sensitive ingénue thief who runs afoul of Hyakkimaru while he is in pursuit of a jorōgumo (a type of yōkai who can take the shape of a beautiful woman, but whose true form is that of a monstrous spider) which claimed one of Hyakkimaru's legs as its price for lending its aid to Kagemitsu.

Like Hyakkumaru, Dororo "earns" her name rather than simply being born with one. She remains unfazed by the fact that Hyakkimaru is actually insulting her when he refers to her as "Dororo" (which supposedly means "little monster") or perhaps she doesn't care. It seems a small price to pay in exchange for a life of danger and excitement.

The rest of the film alternates through several misadventures with a portion of the other yōkai and concludes with the inevitable showdown between Hyakkimaru and his father, Kagemitsu.

Dororo finds that lesson insulting as Hyakkimaru is protected from the hardships of poverty. As a homunculus of sorts, Hyakkimaru doesn't need to eat, so he can't appreciate how horrible it is to go hungry. Should Hyakkimaru succeed in killing Kagemitsu, he'll be the heir to Kagemitsu's throne so Hyakkimaru can't appreciate what it is to be poor.

The problem that plagues Dororo is the same one that plagues the previously mentioned (and reviewed) Blood: The Last Vampire and that is laughable special effects. The yōkai in the movie alternately are represented by actors in ridiculous costumes, cringe-inducing models, or some of the most underwhelming CGI since The Mummy Returns. It really is regrettable that such a potentially powerful story is undermined by this technical issue.

The yōkai are a key element of the plotline so you'd think that they'd be presented in a manner proportionate to their relative importance to the story. They don't necessarily have to be so terrifying as to generate nightmares, but you'd hope that a respectable part of the budget would be spent making the yōkai as impressive as possible.

But, we're talking about Japan here; the nation who made an art form out of guys dressed in rubber lizard suits smashing their way though cardboard mock-ups of Tokyo.

The unintentional humor injected in the story by the chuckle-worthy yōkai provides moments of levity which serve the admirable purpose of keeping Dororo from collapsing under the weight of absolute despair (there are some scenes in the movie which are genuinely touching) but even so, it'd be nice if the yōkai provided a bit more menace.

I'm not so dense as not to recognize deliberate camp when I see it. I just think that the profound parts of this movie serve us better than the humorous ones. Dororo is a tale of the struggle between the giving of one's self versus the sacrifice of others to serve one's own selfish desires and that is a timeless morale that everyone should try to appreciate.

It should probably go without saying but Hyakkimaru only tracks down about half of the yōkai during the course of this particular movie, so the promise of sequels is out there. I'd actually like to see how the tale (and the relationship between Dororo and Hyakkimaru) progresses, so here's hoping that a follow-up film comes out very soon.